Modular NLP

Modular Neural Machine Translation

What is modularity?

Modularity can be described as enforcing a principled sparsity in a neural network, in which specific model parameters become active in certain circumstances. In multilingual machine translation, different translation directions can be seen as different tasks and modules may refer to language-specific components that are involved only in certain tasks. A canonical example would be to use language-specific encoders and decoders in a sequence-to-sequence setup. However, the purpose of multilingual models is to benefit from cross-lingual transfer. Therefore it is also desirable that certain parameters are shared to enable such transfer. Finding the optimal setup for combining parameter sharing with task-specific modules is difficult and below we discuss architectures that can be applied in multilingual modular machine neural translation.

The attention bridge model

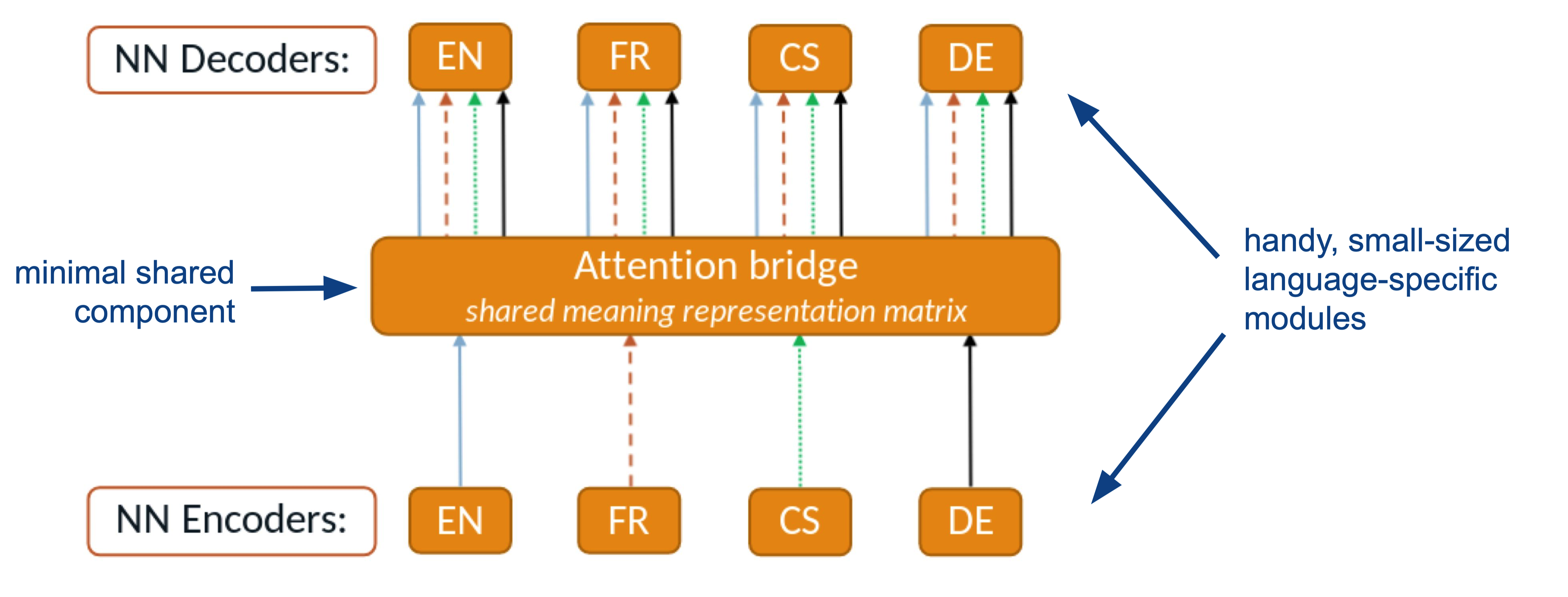

Cífka and Bojar (2018) introduced a fixed-size compound attention that bridges the encoder and the decoder in a typical sequence-to-sequence model used for machine translation. Raganato et al. (2019) extended this model to the multilingual case and implemented a system called the “attention-bridge model”. Here is a high-level image illustrating the idea:

Language-specific encoders produce fixed-size representations through a shared final inner-attention layer. Language-specific decoders access only this information when producing the translations. The idea is to create a cross-lingual bottleneck that needs to be used for each combination of languages during training forcing the model to create multilingual representations that can bridge arbitrary languages. Vázquez et al. (2020) demonstrate that this model can perform translation in supervised and zero-shot scenarios stressing the effective modularization that can be achieved with this setup.

The advantage of the model is that encoders and decoders can be small individually and may operate independent of each other. The active network only involves the selected language-specific component and the shared attention bridge. However, translation performance depends on the size of the attention bridge (in terms of the number of heads and their dimensions). There is also an effect of input length as the attention bridge implies a fixed-size representation, which can lead to a degradation in performance with growing input sequences.

Partially shared components

An alternative to bridging structures for parameter sharing is to divide network into shared and language-specific components. Purason and Tätter (2022) experiment with multilingual neural MT models of varying amounts of parameter sharing. They differentiate between languag-specific encoders and decoders, group-wise shared layers and universally shared layers. Here is an illustration from their paper:

Boggia et al. (2023) take another systematic look on partial parameter sharing in such a setup and study the effect of increasing language coverage on task fitness, language-independence of the shared representations and semantic content. The conclusion is a careful design for parameter sharing is essential to optimize performance and representation learning.

The MAMMOTH framework

The MAMMOTH framework takes the approaches discussed above and integrates them in a flexible framework to allow systematic experiments with different architectures and setups. It implements

- various types of attention bridges

- various types of parameter sharing strategies

- a framework for scalable distributed training

- tools for efficient task allocation and system configuration

MAMMOTH is in heavy development at the University of Helsinki. On-going hyper-parameter tuning and neural architecture search will reveal reliable settings that can be recommended for large-scale model training. MAMMOTH models will also be trained and released from the project. The modular architecture will support efficient inference with selected components.